I spent the whole of last week with police officers from eight African countries attending a senior commanders’ course at the Police Academy, sharing views on the idea and history of development and how these affect police effectiveness.

I found the police officers to be intellectually engaging, knowledgeable, disciplined and clearly aware of their central role in the development and reproduction of cohesive and sustainable states through keeping law and order.

Yet, a look around the continent reveals sustainable law and order remains problematic in many countries. In fact, in some cases, cycles of lawlessness have threatened even the very existence of some states and led to the collapse of governments.

In recent times, we have seen the Arab Spring leading to the toppling of leaders in countries like Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, and Libya. We also continue to see mayhem in Somalia, the Central African Republic, South Sudan, etc.

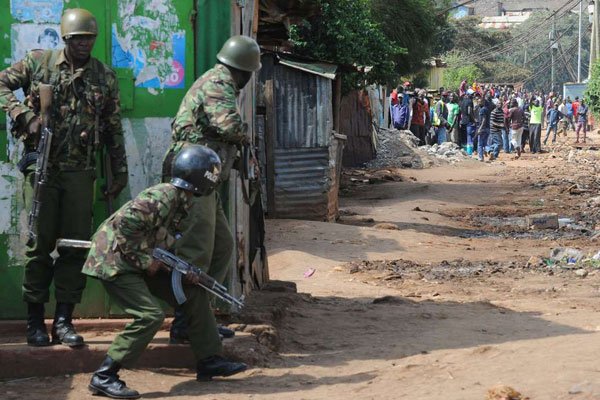

Even as you read this, police in Burundi, Uganda, Kenya, Togo, etc are struggling to maintain sanity.

So, if the police know what they need to do to keep the peace, why does sustainable order remain elusive in many countries?

Of course, there are some who locate the problem internally and relating to lack of professionalism; corruption and mistreatment of citizens on the part of the police while others blame terrorism, a limited budget, poor pay, etc.

From the development point, however, I would say that the primary challenge to effective policing is the securitisation of political disagreements and policing political “enemies.”

Broadly, this challenge relates to three primary failures in most post-colonial countries. The first is the failure to demarcate the boundary between the state and government or ruling parties. The second is failure to construct common citizenship based on equal treatment and finally political interference that encourages and rewards police partisanship.

The boundary between the state and the party in government would mean that the police, which is located in the former and is supposed to be permanent, would only serve interests of all citizens; not interests of ruling parties or politicians in government.

However, often, the boundary between the state, and the party in government is not clear and, in some cases, these are fused.

And since command and control of the police is in most cases under the leadership of a politician in this or that ministry, the police is used to fight political wars; which inevitably invites a bad name for the force and divides nationals.

In fact, that’s why, in many countries, including in the Uganda of today; Kenya and Burundi, the police is more troubled, not when it is fighting ordinary crimes, but whenever there are political disagreements between the opposition and the ruling party or in the election season.

From a historical perspective, this challenge is an inheritance from the colonial police and the immediate post-colonial police forces.

The colonial police was heavily racialised with whites at the top, Asians in the second tier and Africans below. The force was paid only to defend the interests of the colonial government; white privileges and black exploitation.

After Independence, single party rule took over, fusing the state and government with the police largely serving interests of the leader and his party not the nation.

In the third wave of democratisation in the 1990s, hope was restored but, despite reforms, command and control of the police remained in the hands of partisan politicians; with the head of police and deputies appointed by politicians and answerable to them.

With the temptation to remain in power on the part of most leaders on the continent causing endless violent contestations, it’s illusionary to expect the police to remain neutral or to effectively crush dissenters in the long term.

To that extent therefore, the primary challenge to law and order isn’t internal to the police; it’s external and political. In other words, it’s the failure on the part of political leaders to build viably effective and cohesive social, cultural, economic and political communities.

And unless the police becomes apolitical, sustainable law and order will remain problematic.

By Christopher Kayumba for The East African