Video of George Floyd’s last conscious moments on earth horrified the nation, spurring protests that have led to curfews and National Guard interventions in many large cities.

But for the black community in Minneapolis — where Mr. Floyd died after an officer pressed a knee into his neck for 8 minutes 46 seconds — seeing the police use some measure of force is all too common.

About 20 percent of Minneapolis’s population of 430,000 is black. But when the police get physical — with kicks, neck holds, punches, shoves, takedowns, Mace, Tasers or other forms of muscle — nearly 60 percent of the time the person subject to that force is black. And that is according to the city’s own figures.

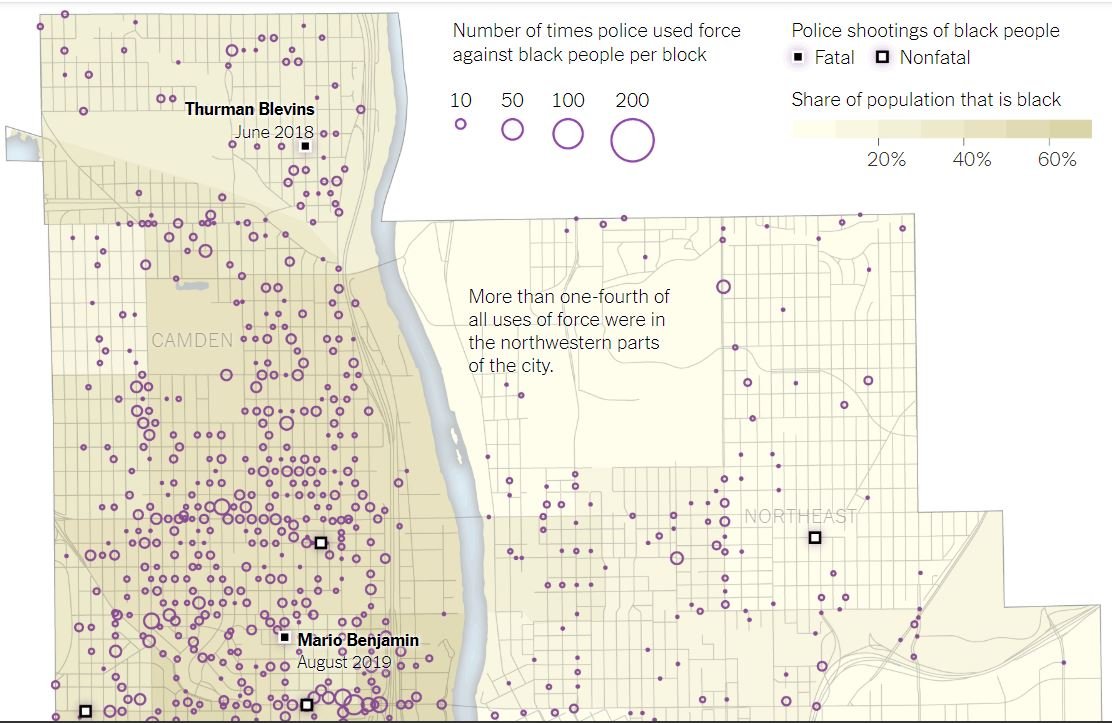

Police shootings and use of force against black people in Minneapolis since 2015

Community leaders say the frequency with which the police use force against black residents helps explain a fury in the city that goes beyond Mr. Floyd’s death, which the medical examiner ruled a homicide.

Community leaders say the frequency with which the police use force against black residents helps explain a fury in the city that goes beyond Mr. Floyd’s death, which the medical examiner ruled a homicide.

Since 2015, the Minneapolis police have documented using force about 11,500 times. For at least 6,650 acts of force, the subject of that force was black.

By comparison, the police have used force about 2,750 times against white people, who make up about 60 percent of the population.

All of that means that the police in Minneapolis used force against black people at a rate at least seven times that of white people during the past five years.

Those figures reflect the total number of acts of force used by the Minneapolis police since 2015. So if an officer slapped, punched and body-pinned one person during the same scuffle, that may be counted as three separate acts of force. There have been about 5,000 total episodes since 2015 in which the police used at least one act of force on someone.

The disparities in the use of force in Minneapolis parallel large racial gaps in vital measures in the city, like income, education and unemployment, said David Schultz, a professor at Hamline University in St. Paul who has studied local police tactics for two decades.

“It just mirrors the disparities of so many other things in which Minneapolis comes in very badly,” Mr. Schultz said.

When he taught a course years ago on potential liability officers face in the line of duty, Mr. Schultz said, he would describe Minneapolis as “a living laboratory on everything you shouldn’t do when it comes to police use of force.”

Police-reported uses of force in Minneapolis by year

Mr. Schultz credits the current police chief, Medaria Arradondo, for seeking improvements but said that in a lot of respects the department still operates like it did decades ago.

“We have a pattern that goes back at least a generation,” Mr. Schultz said.

The protests in Minneapolis have also been fueled by memories of several black men killed by police officers who either never faced charges or were acquitted. They include Jamar Clark, 24, shot in Minneapolis in 2015 after, prosecutors said, he tried to grab an officer’s gun; Thurman Blevins, 31, shot in Minneapolis in 2018 as he yelled, “Please don’t shoot me,” while he ran through an alley; and Philando Castile, 32, whose girlfriend live-streamed the aftermath of his 2016 shooting by police in the suburb of St. Anthony.

The officer seen in the video pressing a knee into Mr. Floyd’s neck, Derek Chauvin, was fired from the force and charged with manslaughter and third-degree murder. Minneapolis police officials did not respond to questions about the type of force he used.

The city’s use-of-force policy covers chokeholds, which apply direct pressure to the front of the neck, but those are considered deadly force to be used only in the most extreme circumstances. Neck restraints are also part of the policy, but those are explicitly defined only as putting direct pressure on the side of the neck — and not the trachea.

“Unconscious neck restraints,” in which an officer is trying to render someone unconscious, have been used 44 times in the past five years — 27 of those on black people.

For years, experts say, many police departments around the country have sought to move away from neck restraints and chokeholds that might constrict the airway as being just too risky.

Types of force used by Minneapolis police

Dave Bicking, a former member of the Minneapolis civilian police review authority, said the tactic used on Mr. Floyd was not a neck restraint under city policy because it resulted in pressure to the front of Mr. Floyd’s neck.

If anything, he said, it was an unlawful type of body-weight pin, a category that is the most frequently deployed type of force in the city: Since 2015, body-weight pinning has been used about 2,200 times against black people, more than twice the number of times it was used against whites.

Mr. Bicking, a board member of Communities United Against Police Brutality, a Minnesota-based group, said that since 2012 more than 2,600 civilian complaints have been filed against Minneapolis police officers.

Other investigations have led to some officers’ being terminated or disciplined — like Mohamed Noor, the officer who killed an Australian woman in 2017 and was later fired and convicted of third-degree murder.

But, Mr. Bicking said, in only a dozen cases involving 15 officers has any discipline resulted from a civilian complaint alleging misconduct. The worst punishment, he said, was 40 hours of unpaid suspension.

“That’s a week’s unpaid vacation,” said Mr. Bicking, who contends that the city has abjectly failed to discipline wayward officers, which he said contributed to last week’s tragedy. He noted that the former officer now charged with Mr. Floyd’s murder had faced at least 17 complaints.

“If discipline had been consistent and appropriate, Derek Chauvin would have either been a much better officer, or would have been off the force,” he said. “If discipline had been done the way it should be done, there is virtually no chance George Floyd would be dead now.”

The city’s use-of-force numbers almost certainly understate the true number of times force is used on the streets, Mr. Bicking said. But he added that even the official reported data go a long way to explain the anger in Minneapolis.

“This has been years and years in the making,” he said. “George Floyd was just the spark.”

Fears that the Minneapolis police may have an uncontrollable problem appeared to prod state officials into action Tuesday. The governor, Tim Walz, a Democrat, said the State Department of Human Rights launched an investigation into whether the police department “engaged in systemic discriminatory practices towards people of color” over the past decade. One possible outcome: a court-enforced decree requiring major changes in how the force operates.

Announcing the inquiry, Governor Walz pledged to “use every tool at our disposal to deconstruct generations of systemic racism in our state.”

While some activists believe the Minneapolis department is one of the worst-behaving urban forces in the country, comparative national numbers on use of force are hard to come by.

According to Philip M. Stinson, a criminologist at Bowling Green State University, some of the most thorough U.S. data comes from a study by the Justice Department published in November 2015: The study found that 3.5 percent of black people said they had been subject to nonfatal force — or the threat of such force — during their most recent contact with the police, compared with 1.4 percent of white people.

Minneapolis police officials did not respond to questions about their data and use-of-force rates. In other places, studies have shown disparate treatment of black people, such as in searches during traffic stops. Some law enforcement officials have reasoned that since high-crime areas are often disproportionately populated by black residents, it is no surprise that black residents would be subject to more police encounters. (The same studies have also shown that black drivers, when searched, possessed contraband no more often than white drivers.)

The Minneapolis data shows that most use of force happens in areas where more black people live. Although crime rates are higher in those areas, black people are also subject to police force more often than white people in some mostly white and wealthy neighborhoods, though the total number of episodes in those areas is small.

Mr. Stinson, who is also a former police officer, said he believes that at some point during the arrest of Mr. Floyd, the restraint applied to him became “intentional premeditated murder.”

“In my experience, applying pressure to somebody’s neck in that fashion is always understood to be the application of deadly force,” Mr. Stinson said.

But equally revealing in the video, he said, was that other officers failed to intercede, despite knowing they were being filmed. He said that suggests the same thing that the use-of-force data also suggest: That police in the city “routinely beat the hell out of black men.”

“Whatever that officer was doing was condoned by his colleagues,” Mr. Stinson said. “They didn’t seem surprised by it at all. It was business as usual.”

Source: The New York Times